A good nose for the essence

- D-CHAB

- LAC

- Highlights

A coincidence led him to industry, a coincidence back to university. In both cases, however, Antonio Togni owes his success mainly to his good instinct for research topics and mentors. Now he is retiring. In this interview, the organometallic chemist tells us, how he built his scientific career on the back of two molecules, how he was pushed to his personal limits as Prorector Doctorate, and why the top of a mountain is not necessarily the final goal.

Professor Antonio Togni likes to stand on mountain peaks – he appreciates nature, the thrill of gravity at high altitudes. Scientifically, the researcher from Graubünden has also reached a "summit" with a good view: He can look back on 22 successful years as a full professor at ETH, during which he has done a lot of research and played a major role in shaping the curriculum of the teaching diploma and the doctorate. But if you ask Togni how he got there, he just smiles: he had never thought about a professorship. As a doctoral student, this summit seemed simply unattainable to him. However, Togni always managed to be in the right place at the right time and to have a good nose – for research questions in the area of enantioselective catalysis as well as for good mentors and opportunities.

As a postdoc, he was sent to the California Institute of Technology "like a package": "Everything was prepared. I just had to say yes," Togni recalls with a voice as if he still could not believe it. However, the postdoc position in the extremely competitive environment of the U.S. was not very helpful; on the contrary: the Americans' exuberant self-confidence made him uneasy. "It took a while to realize that all that glitters is not gold there, either."

The industry and the sense of the essential

Back in Switzerland, Togni got the opportunity to go into industry and joined the Central Research Laboratories of the former Ciba-Geigy Ltd. – a very pivotal experience. There he was mainly responsible for the development of new catalytic enantioselective reactions and the necessary chiral ligands (the involved catalysts are able to recognise the handedness of molecules and steer the preferred formation of one of two mirror images). "I was told on the first day what they wanted me to do and the next stage was the annual report. There, I learned what it really means to let people work independently. I thrived, and over time my confidence grew – as well as my nose," Togni jokes, "the industry sharpened my sense of smell for what's important."

Apart from recognizing and seizing given opportunities, the "important" consisted mainly of not getting bogged down with experimental dead ends, but venturing new approaches as soon as possible. It was all about thinking ahead from what was known in practice, and developing new reactions from it, which, ideally, had again a certain potential for practical application. In fact, Togni's scientific career can be represented by two types of molecules: 1. chiral ferrocenyl ligands and 2. hypervalent iodine reagents.

One career, two types of molecules

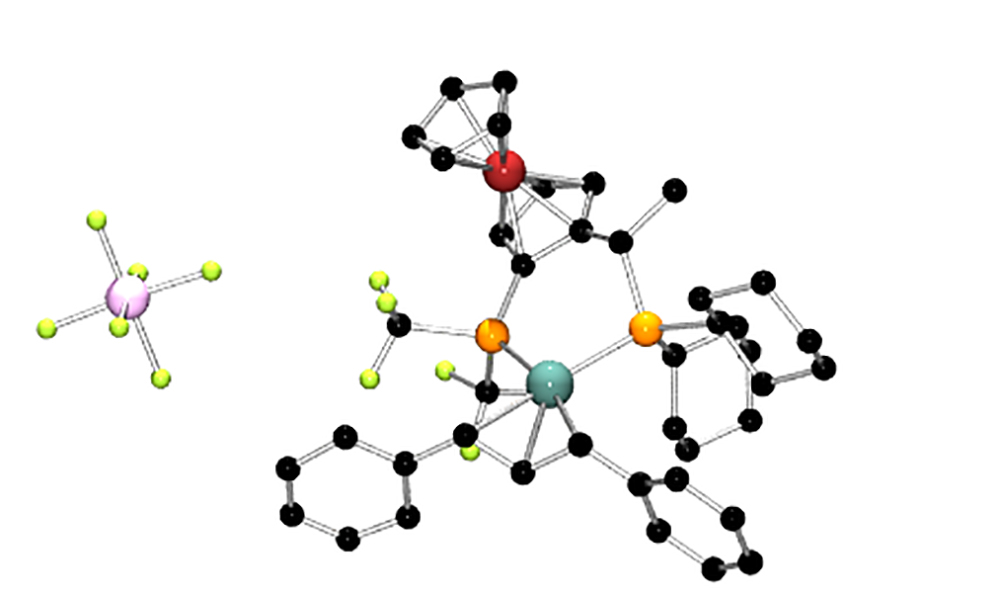

Still at Ciba-Geigy, Togni and the team had further developed so-called ferrocenes – organometallic compounds with aromatic ligands and a central iron atom – and demonstrated their applicability in various reactions. "For example, a herbicide from Syngenta with billion-dollar sales is still being made using a catalyst containing one of these ferrocenyl ligands," Togni says, "fortunately, we had patented the ligands beforehand."

As Ciba-Geigy was facing big changes, Togni was able to take once again advantage of a coincidence and his contacts. An offer brought him back to academia as an external lecturer – first to the University of Zurich, then to ETH Zurich. There, he started his assistant professorship not only with his own substances, which he had brought in vials from Ciba-Geigy, but also with a good set of publications in his luggage, and his first doctoral students – even before the position was official.

The start-up phase was successful. His group continued to work on ferrocenyl ligands, including external page Josiphos – a type of ligand that Togni's lab assistant Josephine had synthesized. He named the ligand after her, which promptly became a new trend among colleagues. In addition, in the '90s, people were also looking for additives that could affect the selectivity of catalytic reactions, Togni says: "With fluoride, we had a huge surprise."

Organofluorine compounds are important for industry, e.g. in drugs or crop protection agents. In 2000, Togni's group developed the first external page enantioselective catalytic fluorination. "Later on, I wanted a to extend this chemistry to the trifluoromethyl group – but the reagents for that did not exist until we discovered the solution: external page hypervalent iodine reagents," Togni explains. These reagents quickly attracted commercial interest after publication in 2006. To date, Togni's group has continued to foster further developments in fluoroorganic chemistry.

The joys and sorrows of teaching and the doctorate

At ETH Zurich, Antonio Togni is also well known for his great commitment to teaching – also in training teachers or concerning the development of doctoral studies. "I became interested in teaching at the “Gymnasium” when my children entered highschool," Togni says with a laugh. Even before the external page HSGYM – initiative Dialog an der Schnittstelle Hochschule-Gymnasium – he and his colleagues were already organizing colloquia for teachers. Later, he contributed to the reform of the teaching diploma at ETH Zurich in the field of chemistry and developed a new course on "the latest research in chemistry, but with relevance to highschool teaching." He points to a colorful script in front of him on his desk: "Giving this lecture is tremendous fun," he says.

Meanwhile, serving as Prorector for Doctoral Studies turned out to be less entertaining. Since 2016, he has had to conduct many difficult discussions for which he was not prepared at all – a mental burden, often carried home after work. If one asks him, whether the doctorate has changed or not, the answer comes quickly: "Yes it has, and so have the doctoral students. They are more determined, they appreciate independence, but also want good supervision." At the same time, however, they are under greater pressure. It is all about publish or perish, Togni says. He observed that in his group too: "People come to my group, because this pressure does not exist here." Quality of work has always been the most important to him, as well as a good mentoring relationship – "people should work with me, not for me."

"People should work with me, not for me." Prof. Antonio Togni

Togni is taking retirement in stride. He will continue to teach some courses, and as far as research is concerned, he states: "I've done what I could. It's time for younger colleagues." For now, his plan is to have no plan – except to continue climbing mountain peaks in his spare time, only to sprint then downhill as fast as he can. This is what he always looks forward to the most – "the steeper, the better!"