Opium, Hashish and Co

Pleasure, addiction, healing: some substances are multi-talented, but there is a fine line between harm and benefit. During a foray through Hartwich's collection, we take a historical and chemical look behind the curtains of opium, hashish & Co.

Opium – a special drug

‘Opium cures everything except itself’, it is said in the Orient. It is a cure and a drug. An old-known substance, "awakening and rapturing," which "breaks out the fangs of thoughts and memories," as Gelpke puts it, and further: the consciousness "stretched like tentacles to the outside world, turns away and closes the windows." No magic, but a lot of chemistry, hidden in the white poppy juice, and a long tradition – this also fascinated Prof. Carl Hartwich.

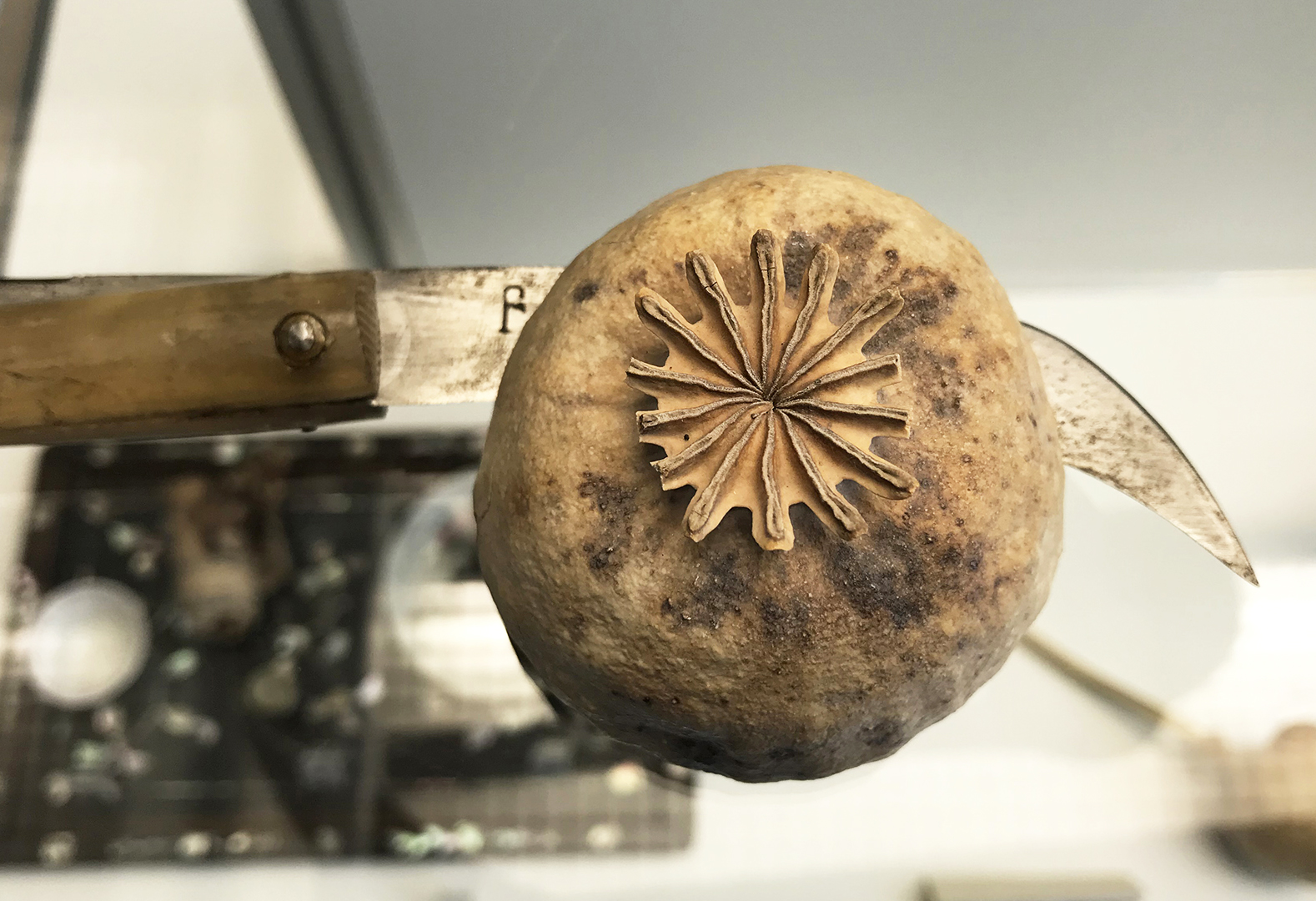

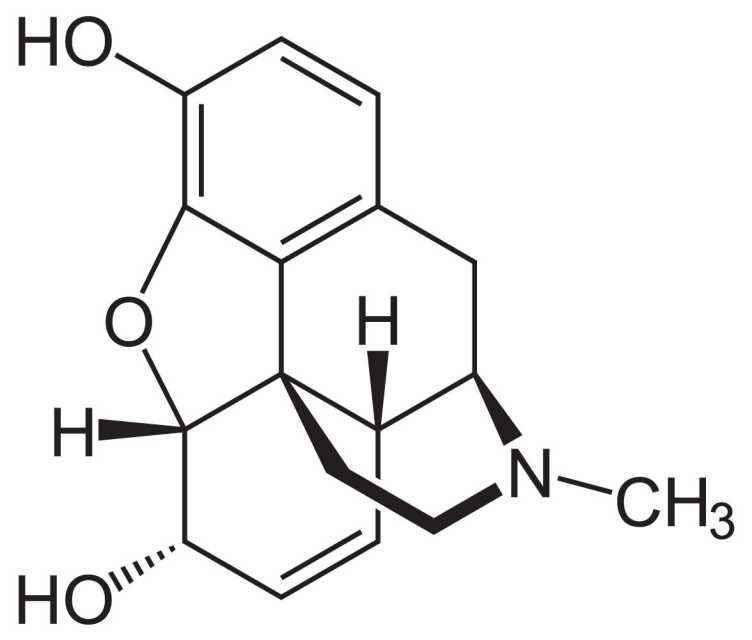

Opium has been extracted from opium poppies (Papaver somniferum L.) for centuries. When the capsules are scratched, the lactic juice emerges and dries. Autooxidation produces a dark pulp – the raw opium, which can now be harvested. Its effect on the human body is due to the alkaloids it contains – heterocyclic, organic compounds with one or more nitrogen atoms, often of plant origin. The best known and proportionally most common is morphine, one of the strongest painkillers. Among other things, it is the starting material for diacetylmorphine, known as heroin. The opium alkaloid codeine, in turn, is still used today as a cough suppressant. In the body, opium alkaloids target specific receptors that are normally intended to mildly dull pain and stress. In the case of morphine, however, the receptors are all activated at the same time, which explains the strong effects. At the same time, dopamine release increases, especially in the body's reward center, an effect with an addictive factor.

The methods on how to obtain this effect are as varied as the cultures that discovered opium for themselves. The Egyptians were already familiar with it, and so were the Greeks and Romans. In the 7th century, opium was spread by the Arabs to India and Persia, and later to China, where it was smoked and became a popular drug in the 17th century through English trade activities. According to Hartwich, an addict consumed up to 80 pipes of chandu (smoked opium) per day. From China, the opium wave then reached Europe.

More details on Hartwich's opium collection as well as on his other "intoxicating" study objects such as hashish, betel, cocoa, coffee, or arrow poison can be found in the collection at HCI or on our corresponding guided tour (Public Tours), see YouTube Video below.

Virtual chat about opium, hashish, betel and Harry Potter's mandragora (mandrake)

Hartwich C. (1911): Die menschlichen Genussmittel. Ihre Herkunft, Verbreitung, Geschichte, Bestandteile, Anwendung und Wirkung. Chr. Herm. Tauchnitz: Leipzig.

Gelpke R. (2008): Vom Rausch im Orient und Okzident. Anaconda Verlag: Köln