The man who turned atomic nuclei into spies

- D-CHAB

- LAC

- LPC

- LOC

- IPW

- Highlights

- ICB

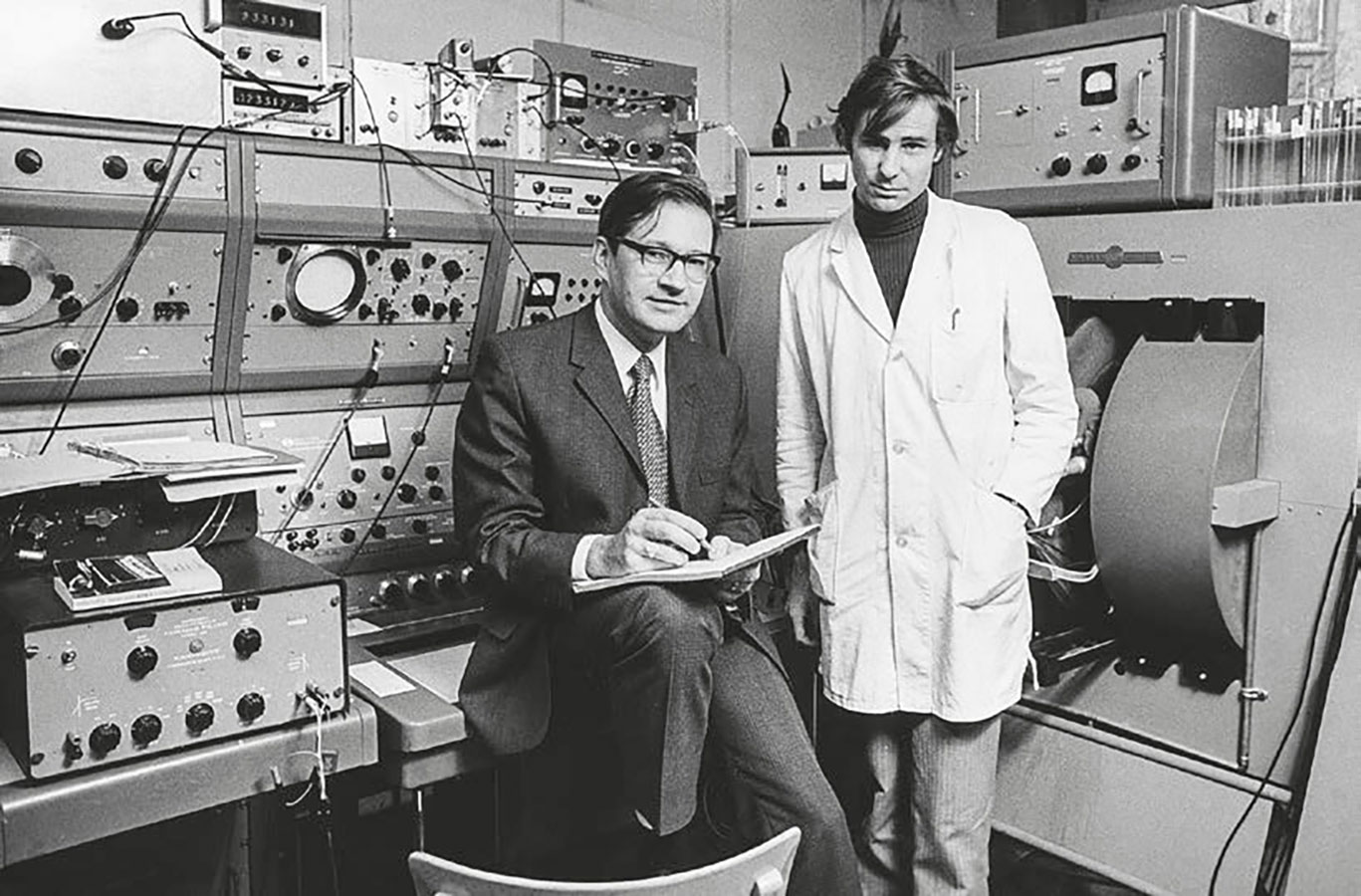

When dancing or driving a car, people usually certified him a lack of technical talent. But in the laboratory Richard R. Ernst has always been one step ahead of the technology of his time. The Nobel Laureate for chemistry has revolutionized diagnostics in medicine with his groundbreaking research on nuclear magnetic resonance, even though it was a rocky road. Now, he published his autobiography in order to inspire others.

Most people have never been in the lucky situation that a pilot invites them into the cockpit during a flight. However, this is actually happened to Richard R. Ernst in 1991. While sitting between the pilots, he could hardly believe the voice on the phone: he just has won the Nobel Prize for chemistry.

Richard R. Ernst begins his recently published autobiography with the description of this moment. It is the portrait of a successful, but also self-critical, restless scientist who devoted his whole life to research - with many ups and downs. He seemingly never lost his sense of humor. Ernst, born in Winthertur in 1933, entertains the reader with the story of his difficult childhood and the pivotal discovery of an old box with chemicals in the attic – unaware that at the same time the Swiss physicist Felix Bloch laid the foundation of the subject that would later become his area of expertise.

Ernst talks about his time at ‚Gymnasium‘(secondary school), which he only remembers as a time of "mental and intellectual torture" because he hated all language subjects. He tells the reader about the chemical internships at ETH, which regularly covered him in "disgusting odors", scaring off women on the train home. Even without the odor, he always felt to engage in a "military exercise" when asking girls to dance with him, not to mention dancing itself. Ernst often disappeared into the bathroom to look up the dancing steps in his notes. Even his driving instructor certified him a lack of technical talent – quite embarrassing to the young man, who solved every day difficult technical problems at ETH Zurich.

Nuclear magnetic resonance as lifebelt in the "shark tank"

From a career point of view, things went well for the shy student. However, he soon realized that he must be "better and different than others" in order to survive the academic "shark tank". Therefore, Ernst chose one of the most difficult niche topics at that time: nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). NMR is a method where atomic nuclei, usually hydrogen nuclei, are exposed to a strong magnetic field and irradiated with radiofrequency. After irradiation, the nuclear spins revert to their original state and release the absorbed energy in the form of radio waves. This way, Ernst says, "the magnetic nuclei operate like spies. They reveal information about the molecule in which they are embedded." But at that time, nobody could imagine “that this method would be used for solving structures of chemical substances and that it would revolutionize imaging in medicine.”

For almost 30 years, Ernst spent all his energy and time to improve the work of these molecular "spies": he reduced the signal-to-noise ratio, increased the information output, and eventually applied the method to imaging. Today, almost every hospital has an instrument for NMR imaging. Ernst received the Nobel Prize for his work – undoubtedly the highlight of his career. But he paid with the renouncement of his personal needs, the neglect of his wife and children, a mental breakdown, and an enormous burden resting on his shoulders: occupational stress, pressure, and the feeling that he wrongly received the award without the Swiss chemist Kurt Wüthrich who played a decisive role for the success of this method (Wüthrich received the Nobel Prize in 2002).

Today, Ernst is convinced that scientists need at least two pillars to make progress and find the necessary balance. His second pillar is his passion for collecting and restoring Tibetan scroll paintings on which he published as well. In his opinion, interdisciplinarity is essential, but educational institutions unfortunately prefer to turn their students into “well lubricated cogs in the wheelwork of society". But researchers are not "exotic orchids" for the sole benefit of "pleasing society”, Ernst states. Science today needs critical minds that are able and motivated to share their research with the public. However, Richard R. Ernst’s book is not supposed to be "a moral lecture or a textbook on nuclear magnetic resonance", but it is "simply a book about my own life", which could ideally inspire "other people on their way to self-awareness".

Further information:

Ernst, R. Richard (2020): Richard R. Ernst. Nobelpreisträger aus Winthertur. Autobiographie. Hier und Jetzt, Verlag für Kultur und Geschichte GmbH: Baden, Schweiz

external page Video Trailer to Richard Ernst and his autobiography