The chemistry of fragrances

Fragrances, whether natural or synthetic, evoke memories and emotions, are daily companions as well as tools of communication – but how do they work? What made the scent of a sperm whale so popular? And what exactly are olfactory chemists doing?

What was the scent of ancient Egypt? At least we know that there were already papyrus scrolls with perfume recipes and rites for embalming the dead with fragrant resin. From the Orient, perfumery eventually spread to France and found its center in flower-rich Grasse. However, flowers and essential oils are not the only sources of scent. Animals also produce fragrances. The dark, waxy ambergris, for example - which can also be found in our collection in the HCI - used to come from the digestive tract of the sperm whale. If the substance enters the sea, chemical reactions take place and form a fragrant ambergris body – once as precious as gold. Today, ambergris is synthesized artificially.

Perfumers are also fond of musk deer. The males have a musk pouch, which contains a fragrant rutting secretion. This was also traded at high prices, because musk is the sensual-erotic core of a perfume and gives a feeling of well-being. Today perfumers use artificial forms.

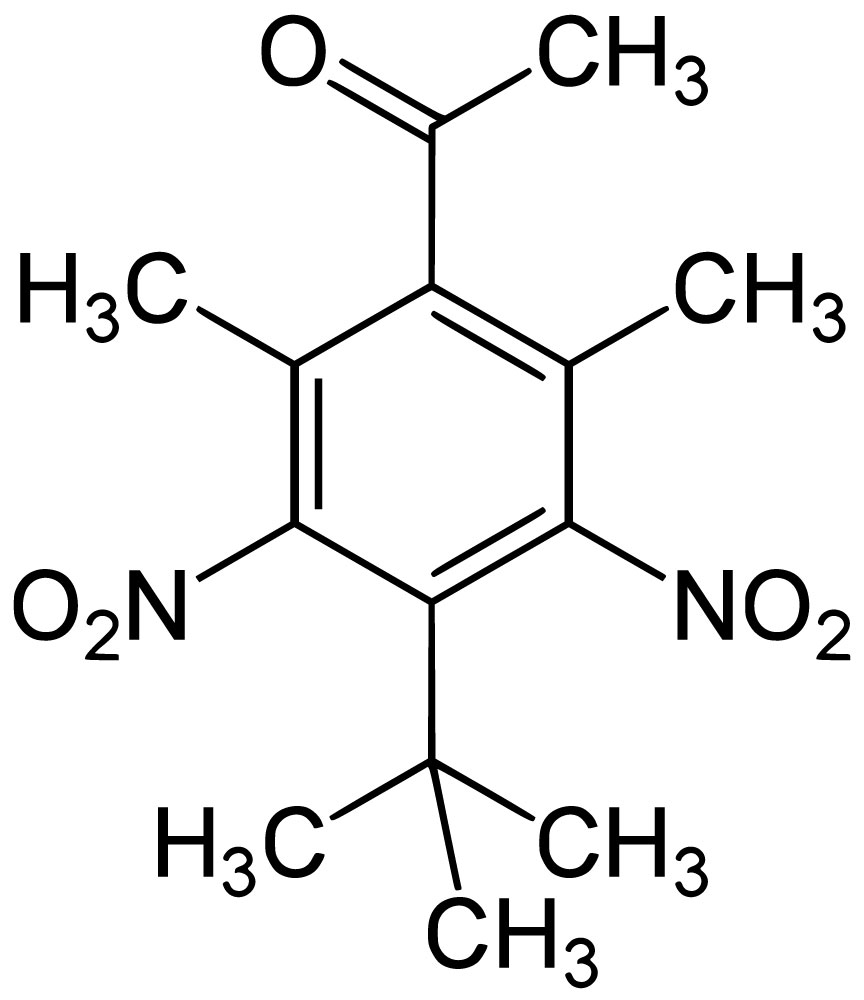

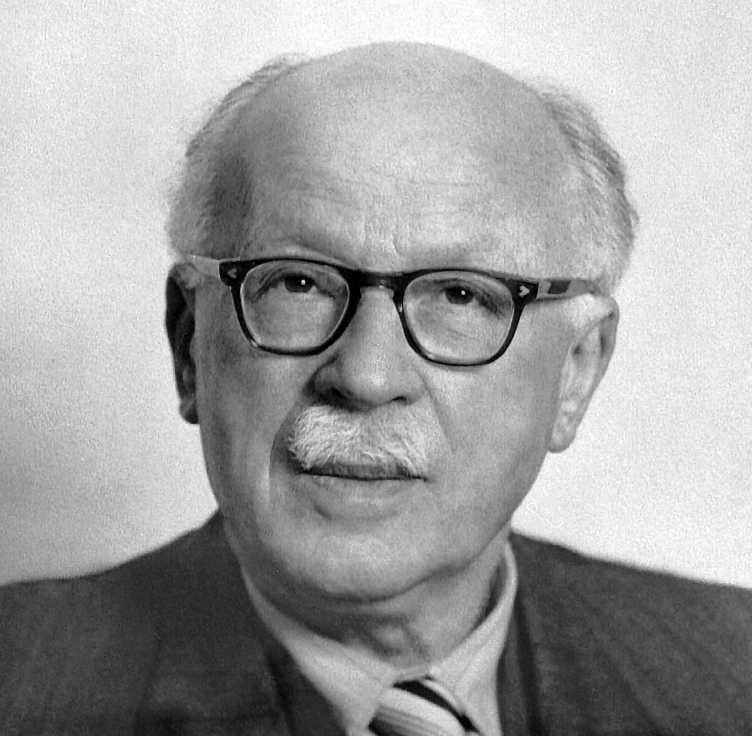

Musk belongs to the class of terpenes. These are characterized by a ring structure. The former ETH professor and later Nobel Prize winner Leopold Ruzicka discovered that these rings can have up to 17 members – as can muscine (from the musk deer) or civetine (fragrance of the civet cat), both used by perfumers at that time. Ruzicka was also able to synthesize the substances – thus heralding in the age of macrocyclic fragrances – and provided important raw materials for the perfumes of the company Naef & Cie (later Firmenich). To this day, musk bodies form a central part of fragrance research.

Fragrance research also deals with the interaction of structure and smell, because scents function in a very complex way. They are picked up by olfactory sensory cells and their receptors in the nasal mucosa. The stimuli are passed on to the brain, where they create a scent image that is individual to each person. The system is still largely not understood. Therein lies the challenge for olfactory chemists: they must constantly discover new compounds, in other words scents, which must also be harmless to humans and the environment.

The lord of the carbon rings

Leopold S. Ruzicka (1887–1976) originated from Vukovar, Croatia. The chemist conducted research and taught in Utrecht and Zurich, and from 1929 was permanently at ETH Zurich. In between, he also worked for the Geneva perfumers Chuit, Naef & Firmenich – original vessels from that time can be found in the collection. Ruzicka's merit lay above all in the structural elucidation of complex natural substances, such as terpenes. He was able to show that ring-shaped molecules with more than eight members exist and also managed to synthesize them. He also conducted research on steroids and was able to isolate the male sex hormones androsterone and testosterone. In 1939 he received the Nobel Prize for his work on polymethylenes and terpenes.

Literature and reading tips

Download Armanino et al. 2020: Heiße Luft oder cooler Duft? Die Trends der letzten 20 Jahre in der Riechstoffchemie (PDF, 27.5 MB). Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 16450–16487. doi.org/10.1002/ange.202005719

Download Brauckmann 2001: Der Struktur von Düften und Aromen auf der Spur. Report. ETH Research Collection. (PDF, 731 KB) doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-004384414

Leopold Ruzicka – Nobelpreis für Chemie 1939. Universität Zürich. Download Artikel (PDF, 542 KB) und external page Video